Deadly Eastern Equine Encephalitis on the Rise: LSU Diagnostics Confirms Surge in Fatal Mosquito-borne Virus in Horses

August 25, 2025

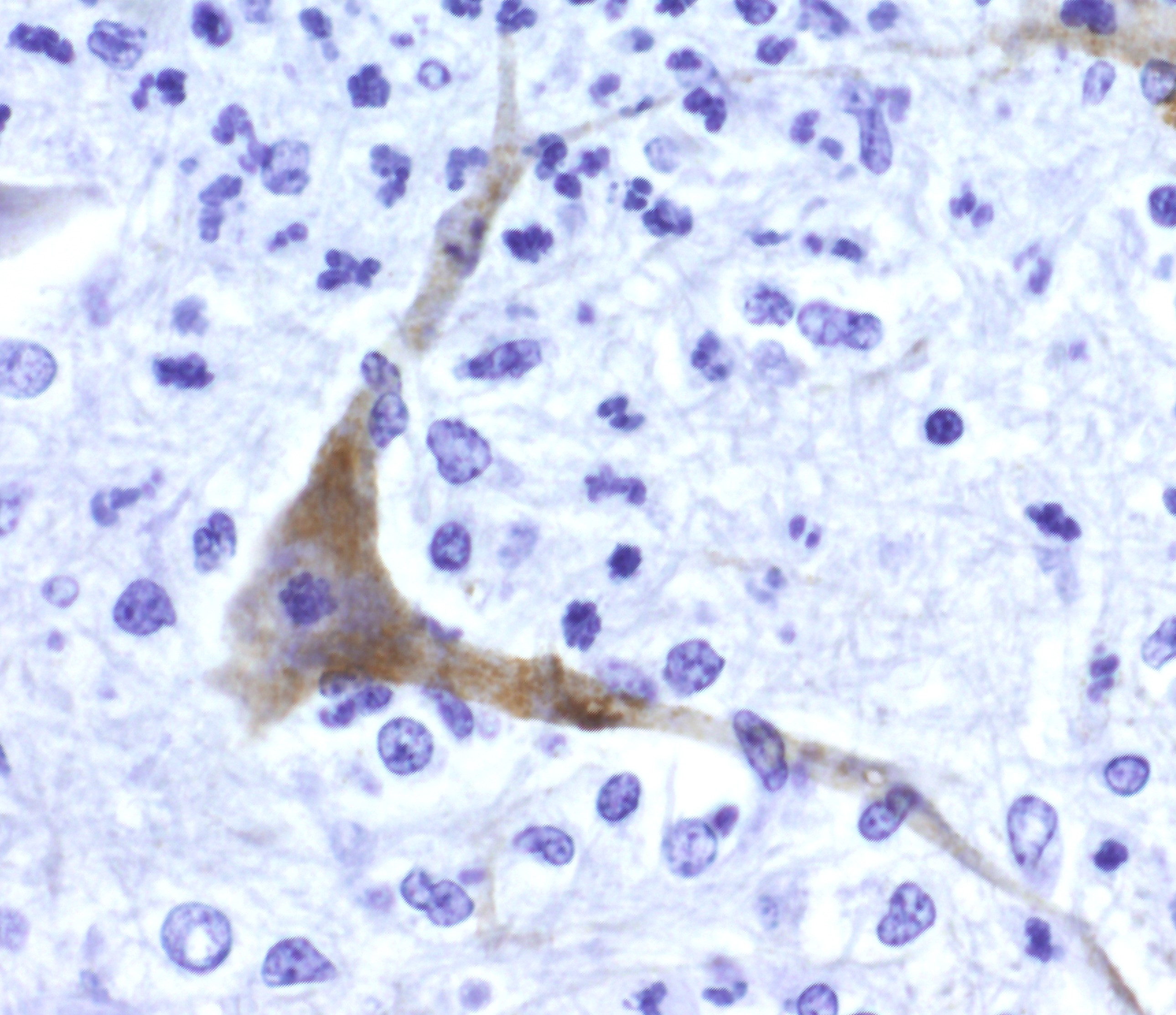

Eastern Equine Encephalitis infecting a horse brain cell.

– Image courtesy of Fabio Del Piero, LSU Diagnostics.

This image of a horse brain cell infected with Eastern Equine Encephalitis (EEE) illustrates the serious risk posed by this deadly mosquito-borne virus. At LSU Diagnostics and within the LSU Vet Med equine team, clinicians are on the front lines—detecting cases and working to prevent further spread.

EEE occurs in the eastern, Gulf Coast, and north-central regions of the United States, as well as parts of Central and South America and the Caribbean. Horses in areas with dense mosquito populations—such as swamps, coastal marshes, and coves—are at heightened risk.

The sedentary black-tailed mosquito (Culiseta melanura) is the primary carrier of EEE among

birds. More active mosquito species serve as “bridge vectors,” spreading the virus

from birds to mammals—including horses, people, dogs, cats, goats, and cattle. While

mammals can become infected, they are dead-end hosts; transmission requires a mosquito

bite.

Louisiana regularly sees mosquito-borne diseases, including both West Nile virus (WNV)

and

EEE. While both can infect horses and humans, LSU Diagnostics has documented an unusual

increase in EEE cases this year.

“Necropsy and serological testing at LSU Diagnostics have confirmed more than 20 positive

cases in horses so far,” said Dr. Alma Roy, interim director of LSU Diagnostics.

EEE is especially severe in horses, with mortality rates up to 90 percent. Survivors often suffer permanent neurological damage. In humans, approximately 30 percent of those with severe EEE die from the infection.

By comparison, West Nile virus tends to be less deadly. Among horses with severe neurologic disease, 30 to 40 percent may die, while about two-thirds recover. In humans, mortality from severe WNV illness typically ranges from 3 to 15 percent.

“Many survive a West Nile virus infection, but EEE can be unforgiving. Be careful,” said Dr. Fabio Del Piero, pathologist at LSU Diagnostics and professor at LSU Vet Med.

Treatment options for both EEE and WNV are limited and largely supportive. Horses showing neurologic signs can be hospitalized at LSU Vet Med. Recently, for example, Dr. Frank Andrews, director of Equine Health and Sports Performance and a professor of equine medicine at LSU Vet Med, and his team successfully managed a hospitalized horse with West Nile virus.

Vaccination remains the most effective protection. Clinicians recommend vaccinating horses at least every six months against EEE and WNV, since Louisiana’s mild winters do not significantly reduce mosquito populations.

“It’s critical that vaccines come directly from a veterinarian,” said Dr. Rose Baker, associate professor of equine medicine at LSU Vet Med. “Vaccines that are improperly stored, such as those bought at feed stores or shipped from the internet, may lose effectiveness. Proper vaccination is incredibly protective, but we see upticks in cases when people become complacent and stop vaccinating their horses.”

Preventing mosquito bites is equally important. This includes personal and environmental measures, such as eliminating standing water and using appropriate repellents. LSU Diagnostics and LSU Vet Med clinicians report positive cases to the Louisiana State Veterinarian’s Office, which coordinates with local health authorities to increase mosquito control in affected areas—protecting both animals and people.

CDC: Mosquito Control Overview

EEE is one of several life-threatening diseases diagnosed by LSU Diagnostics. The team provides rapid, accurate disease detection through tissue and serum testing, as well as post-mortem diagnostics. LSU Diagnostics also supports the statewide mosquito-virus surveillance programs.